Deux visages de L'Astrée

Deux visages de L'Astrée

|

Two faces of L'Astrée, the first critical edition of Honoré d'Urfé's masterpiece, presents the novel and explains its evolution during the author's lifetime. It is a working tool intended for neophytes as well as seventeenth-century specialists. |

Ed. Vaganay**, 1925 See Illustrations |

Just as Honoré d'Urfé's portraits reveal two aspects of his personality and two moments in his career, this edition analyzes two stages of his seminal work with the help of different fonts and colours. L'Astrée has long been considered to be the "first bestseller" of the French narrative literature, according to H.-J. Martin, specialist in the history of the book (p. 481). Yet until the publication of my critical edition, in 2007, readers of the novel have been confronted with huge linguistic and cultural barriers.

Because of its length and complexity, L'Astrée is not only poorly understood, but also almost unknown.

It is, however, the French answer to Montemayor's Diana, Cervantes' Galatea, Sidney's and Sannazaro's Arcadia. With some nine hundred thousand words (Dictionnaire) and some seven hundred proper names (Index), L'Astrée is indeed a difficult work that blends contradictions and unusual assemblages (Synopsis). L'Astrée combines, in a pastoral setting, the romance of Astrée and Céladon with the fall of the Roman Empire and the painful birth of France following the reunion of the Gallic tribes. It requires a substantial and varied critical apparatus to clarify the fifth-century history, the sometime archaic vocabulary, the mythological foundation, Neoplatonic values, Celtic theology, Counter-Reformation ambitions, bold treatment of sexuality, as well as problems due to the author's untimely death - missing closure allowing suspicious additions. In 1925, Hugues Vaganay published a five volume edition of L'Astrée. It has long been a reference, but it does not give any assistance to the readers.

Thanks to the power of electronics, Deux visages de L'Astrée includes nine renditions of the first three parts: the preliminary edition, the reference edition and its modern French version that can be downloaded as a Word document. The novel continuation, a draft published without the author consent, is represented by the 1624 edition of the fourth part (with its modern French version and its Word version).

To read the novel, click on this button:

![]() Lecture de

Lecture de

L'Astrée

For an English synopsis click here.

Deux visages de L'Astrée brings together an encyclopedic documentation because the novel is associated to multiple commentary in order to explore the novel and to explore the author's biography. Readers can investigate the critical and analytical reasoning by following the order suggested by this sign:

is at the beginning and at the end of all documents written in French.

is at the beginning and at the end of all documents written in French.A detailed User guide explains the organization of the site. It also starts a guided tour that passes through all available resources.

This critical edition establishes for the first time that:

1. the standard text that we quote since 1925 is not reliable: Vaganay's L'Astrée is replete with errors

- for instance, Bellinde would have died with Celion η;

2. in 1610, with the publication of the second volume of the novel and the assassination of Henri IV, L'Astrée experienced an essential double shift

- for instance, Céladon does not descend from Pan anymore; his ancestors are now knights η;

3. Honoré d'Urfé did not always carefully review or supervise his drafts

- for instance, Callirée was not supposed to resuscitate η;

4 the 1621 edition of the first three volumes presents the only homogeneous Astrée, endowed with a privilege attributed to Honoré d'Urfé and published during his lifetime with his approval;

5. the inclusion of the preliminary editions (1607, 1610 and 1619) allows scholars to accurately examine the development of the author’s thoughts and the evolution of his style;

6. the unfinished draft published in 1624 as the fourth part is more reliable than the fallacious Vraye Astree of 1627.

Thanks to its highly flexible electronic form, Deux visages de L'Astrée remains a work in progress. It will certainly see additions and modifications. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Music and pictures are not in the public domain and cannot be copied. To quote Deux visages de L'Astrée please name its author, Eglal Henein.

provides the correct reference.

Synopsis

Honoré d'Urfé, L'Astrée

5  L'Astrée relates the adventures of a community whose ancestors chose to distance themselves from wars by becoming shepherds in hamlets along the Lignon River, in Honoré d'Urfé's homeland. The story is set in fifth-century Gaul, in the region of Forez, and the action lasts about six months. Most of the principal characters are young; the heroes are not even twenty years old.

L'Astrée relates the adventures of a community whose ancestors chose to distance themselves from wars by becoming shepherds in hamlets along the Lignon River, in Honoré d'Urfé's homeland. The story is set in fifth-century Gaul, in the region of Forez, and the action lasts about six months. Most of the principal characters are young; the heroes are not even twenty years old.

L'Astrée also recounts the exploits of knights and ladies - called nymphs - who belong to the court of Amasis, the Lady of Forez, and live in Marcilly, the capital. Amasis has two children, Clidaman and Galathée. Three years before the beginning of the novel, Clidaman organized a game of chance to pair off young men with maidens.

Many outsiders visit Forez, most of them dressed as shepherds. They mingle with people who live in the hamlet but not with people who live in the castle. At the end of the fourth volume, some shepherds go to Marcilly with their visitors η.

L'Astrée is a historical novel as evidenced by the Chronologie historique. The political upheavals of the fifth century deeply affect Alcippe, Céladon's father, and two children kidnapped by invaders. (We know them as Silvandre and Paris). Starting in the second volume, the author inserts narratives that evoke the actual detailed history of the fifth century. He introduces the Roman Empire through the Story of Placidie and the Story of Eudoxe, respectively mother and wife of Valentinen III. The beginnings of the Frank domination appear in the Story of Childéric, the son of Mérovée and father of Clovis. In the fourth volume, the Story of Dorinde presents the court of Gondebaud, king of the Bourguignons.

Only one historical short story certainly refers to current events that took place in France at the end of the sixteenth century. The Story of Euric, king of the Visigoths, is a veiled narration of the affair of Henri IV and Gabrielle d'Estrées. This story, placed at the beginning of volume three, was published nine years after the king's assassination.

L'Astrée is a love story. Honoré d'Urfé brilliantly presents all the colors of this "violent passion that nature arouses in young persons of various sexes to join in order to perpetuate the species" as Furetière says in his Dictionnary. No one considers perpetuating the species in L'Astrée, but no one recommends ascetic life. Many characters could take as a motto Equicola's words in his Six Books of the Nature of Love (Book 1, f° 72 recto).

"Love is in us lord and master."

Love pleasures and love sorrows proliferate. They do not produce a syrupy romance, but a novel that may have been considered risqué because of the license allowed by cross-dressing: "Love is treated in a manner so delicate and insinuating, that the bait of this dangerous passion enters easily into young hearts" (Huet, p. 530). Thanks to the youth, leisure and audacity of his characters, Honoré d'Urfé can describe all kinds of romantic relationships, including, at least apparently, homosexual relationships.

The main thing, however, remains the faculty of judging soundly questions of the heart. The novelist, of course, does not refute himself. He remains the author of the Epistres morales when he asks : How will the beloved choose between two lovers? How can one be sure of the feelings of the chosen partner? Honoré d'Urfé dwells on stories of misunderstandings that take on the appearance of tragedy because of jealousy and mistrust cultivated by villains. Will time bring certitude or peace to those torn souls? Hope alone supports those who love, says the novelist who considers hope as love's mother, sister (I, 3, 72 verso), and nanny (I, 10, 327 verso).

L’Astrée is an unfinished novel. The big question will never get a definitive answer. Will these love stories end well? Let's first agree on the meaning of "end well." L’Astrée will certainly not end as an American love movie or as a Molière's comedy, by serial marriages; Laurence Plazenet has established it very convincingly. D'Urfé seems to share Montaigne's opinion: "A good marriage, if there is one, refuses the company and conditions of love: it tries to represent those of friendship" (III, p. 66). The couples that d'Urfé permanently reconciles in his novel get engaged under the benevolent eyes of a druid (Daphnide and Alcidon, Madonthe and Damon) or those of a king (Criséide and Arimant). One couple represents the exception that confirms the rule, Célidée and Thamire marry in front of our eyes without assistance and without supervision. All the other lovers live in expectation - even when nothing seems to prevent marriage, as in the case of Phillis and Lycidas or Doris and Palémon.

Yes, L'Astrée will end well. Jean Du Crozet, in 1593, after reading a draft of the novel, announced:

And Astrée at the end, changing her cruelty,

Of the shepherd Céladon will satisfy the soul,

Anchoring his mast in the desired harbour (p. 115).

The novel will close on happy couples who are not yet indissolubly attached, couples still hoping.

L'Astrée revolves around three plots. The love story of Astrée and Céladon gives the novel its spinal column. The love story of Diane and Silvandre provides a stop watch to indicate the passage of time. The love stories of Galathée supply a calendar mixing the wars of the Frank kings with a dispute over the government of Forez. As for the loves of Hylas, they are interweaved to vary the perspective...

"The time of nature" and "the time of adventure" intertwine in L'Astrée. The first part begins with Céladon's suicide and lasts about six weeks. The second part begins one month after the end of the first, during the summer. It lasts about three months. It serves as a frame for the beginning of Céladon's life as a female druid and for the wager of Silvandre who is supposed to pretend to love Diane for three months. The third part begins in July, three days after the end of the second. It lasts a week or so; the wager ends later than expected. The fourth part starts right after the third and only takes three days.

The passage of hours and days is indicated by the state of the moon and by the meals. The main adventure is destined to conclude soon, as Céladon's disguise must end three or four months after having begun. At that time, Forezian druids will return from their annual meeting, they will have seen the true Alexis and they will be able to unmask the hero. Time is counted. As Honoré d'Urfé writes in his Epistres morales: "It is hoping in vain to think of coming out of this labyrinth of desolation without the help of reason or time" (I, 13, p. 118).

The specific time of adventures does not match well the leaping time of culture, i.e. the precise historical dates of the fifth century. Attila's defeat, Mérovée's death, Euric's and Valentinien's assassination, Childéric's exile and Gondebaud's victories push the readers towards crossroads (see Historical Chronology). When he draws the meanders of time in L'Astrée, Honoré d'Urfé looks under the microscope at the destiny of the Lignon shepherds; he looks through a telescope at the tribulations of foreign kings.

Astrée, Céladon, Diane, Silvandre and Galathée are the five pillars of the novel. Around them gravitate some three hundred characters. Whether they play an important role, such as Laonice, Lériane or Léonide, or a secondary role, such as Aimée, Agis or Proxime, they all appear in the Tableaux des Personnages where their actions are summarised in a fact sheet.

6  The Central and Paramount Intrigue: Astrée and Céladon

The Central and Paramount Intrigue: Astrée and Céladon

In all contexts and in all memories, this emblematic couple eclipses the other characters. It is at the heart of Honoré d'Urfé's work. Thus, in 1666, when a young man in the Roman bourgeois offers the five volumes of the novel to the girl he wants to seduce,

he set himself to re-read L'Astrée, and studied it so well that he admirably counterfeited Céladon. He took this name seeing that it pleased his mistress, and at the same time she took the name of Astrée (Furetière, p. 1007).

Three centuries later, in 1964, it is this couple that catches the attention of an ingenious publisher, Gérard Genette:

We have preserved what offers the most coherence and continuity (and perhaps [...] significance): the loves of Astrée and Céladon (p. 22).

In 2007, for the novel 400th anniversary, Éric Rohmer calls his last film The Romance of Astrée and Céladon, and Louis Bouchet creates a graphic novel based on the love story of Céladon and Astrée.

7  In the first volume, Astrée and Céladon split up.

In the first volume, Astrée and Céladon split up.

At the very beginning of the first book, Astrée, driven by jealousy, banishes Céladon. Céladon throws himself in the Lignon river. He is believed dead. A double story line ensues because the protagonists will live different adventures.

Astrée tells the story of her life to two friends. Although they belong to feuding families, Céladon and she have been in love since their early youth. Their story started on a holy day: the shepherd dressed as a woman to make his first declaration of love to her. In a playful Judgment of Pâris, Céladon (who passes for Orithie) awards the legendary apple to Astrée. For three years, the young couple overcame obstacles imposed by Céladon's father. Shortly after the father's death a new type of obstacle emerged: Semire, a shepherd in love with Astrée, showed her Céladon reciting a poem to another shepherdess. Astrée forgets that she herself ordered her partner to pretend to love another woman. She banished Céladon, and now cries over his death.

Astrée and her companions receive many visitors. Shepherds from other hamlets, shepherds from the city of Paris, and strangers disguised as shepherds. They all tell their adventures. Some request arbitration.

Meanwhile, nymphs - whose name only is mythological - save Céladon found unconscious near the river. They are Galathée, daughter of the Lady of Forez, and her followers. Thus, castle people meet country people and narrate their love stories to entertain Céladon.

Aristocrtic love life is upset by the presence of this too lovable young man. In fact, a fake druid predicted to Galathée that she would love the man she met on the banks of the Lignon. Galathée, falls in love with Céladon and treats him as her prisoner. Actually, the knight Galathée was supposed to meet at the river is Polémas, who has hired the false druid.

In the gardens of Galathée's castle stands an inaccessible fountain of Truth in love. Léonide, one of the nymphs of Galathée suite, and later, her uncle, the druid Adamas, explain to Céladon the history and functions of this legendary monument three times enchanted. Then, Léonide and Adamas help the shepherd regain his freedom by lending him a nymph dress.

Because Astrée had ordered him not to appear before her, Céladon does not return to the village.

8  In the second volume, Astrée and Céladon draw closer.

In the second volume, Astrée and Céladon draw closer.

Now living in a cave, Céladon is once more saved by Léonide and Adamas, as they give him the opportunity and the means to express his sorrow. At the instigation of the druid, Céladon builds in the woods a temple to Astrée, goddess of Justice. There he exhibits an enlargement of a portrait the shepherdess offered him, which he decorates with poems.

Adamas encourages his protégé to elevate his thoughts: he explains to Céladon the mysteries of a tolerant religion that combines Christianity and Druidism. An oracle seems to order the druid to work for the happiness of Céladon. Adamas thus suggests that the young man temporarily take the name and place of his daughter, Alexis, and live with him. This disguise can last only three and a half months, since it must end before the closure of the annual meeting of the druids, for the people of Forez will then know that the real daughter of Adamas is still in her convent. The fake daughter must disappear before.

Meanwhile, Astrée, always surrounded by the people of the hamlet, continues to listen to stories about the more or less appropriate decisions made by lovers.

The alter ego of the novelist, a stranger dressed as a shepherd named Silvandre - silva andros, man of the Forez - mediates between Astrée and Céladon. While Silvandre sleeps in the woods, Céladon leaves on his heart a letter for Astrée. Silvandre shows the letter to the shepherdess and then guides his companions to the place where he received Céladon's letter. As Silvandre loses his way, the group ends up in front of Astrée's temple.

The enlarged portrait and the poems mislead the heroine: Astrée is more than ever convinced that Céladon is dead. She believes the "spirit" of the shepherd built the temple and expressed his love. Céladon nevertheless enjoys a slight reward; he discovers Astrée asleep and steals a kiss. Believing she had a vision, the maiden wants to build a shrine to Céladon's soul. The funeral takes place in the woods, attended by the nymph Léonide and her cousin, Paris.

Shortly after, a delegation of male shepherds goes to Adamas to welcome his daughter, Alexis, who is Céladon dressed as a female druid. The disguise is so perfect that it fools even Céladon's brother. Hylas, the womanizer of the novel, falls in love with the fake druid. Who could doubt the word of Adamas who pretends to be the father of this attractive Alexis ?

9  In the third volume, Astrée and Céladon meet again.

In the third volume, Astrée and Céladon meet again.

At the house of Adamas with her companions, Astrée shows her enthusiastic affection for this Alexis who looks so much like Céladon. During a two day visit, the young couple has intimate conversations. Astrée would like to become a druid to stay with her new friend. Alexis tells her about her love for a young female druid who rejected her. The shepherdess Astrée fails to understand this metaphorical transposition of her romance with Céladon.

Adamas' house is the site of the most astonishing titillating scenes, thanks to the description of bedtimes and awakenings. Alexis has her own room, but in the morning, Léonide brings Astrée to her. The druid, Léonide and Alexis, his fake daughter, then go to the village and stay with Astrée's uncle. This time, the distribution of beds is more delicate. In Astrée's room, Alexis will sleep alone while Astrée will share a bed with Diane, her companion, and Léonide. Astrée's kisses play havoc with Alexis' half resistance. Thus Alexis goes from one extreme to the other: erotic scenes are followed by pathetic monologues because Alexis-Céladon recognizes that she is in an inextricable situation.

Adamas is summoned to the palace with his daughter and his niece. The druid has always carefully avoided any meeting between Alexis and Galathée, knowing that the nymph would be less naive than the shepherds because she is less sensitive to his ascendancy. He decides to go to the capital with Léonide only. Alexis remains with Astrée.

Honoré d'Urfé died leaving L'Astrée unfinished.

Several sequels were published.

The first group, the more reliable, consists of drafts published in 1624, 1625 and 1626.

The second group is due to

Balthazar Baro.

His pseudo Vraye Astree and his Conclusion appeared in 1627 and 1628.

10  In the fourth volume of 1624, Astrée and Alexis are inseparable.

In the fourth volume of 1624, Astrée and Alexis are inseparable.

Alexis and Astrée are still living in complete intimacy. Roles are reversed because they have exchanged names and dresses. Their constant caresses surprise their companions. The fake Alexis, dressed as a shepherdess, is increasingly troubled, physically and mentally, by the favors she receives from Astrée dressed as a female druid. Céladon emerges twice. When a young woman is attacked by a troop of armed men, Alexis fights like a man; Alexis defends the male gender when all men are accused of being unfaithful.

Astrée has a dream that ends with the vision of Céladon. She wakes up screaming the name of the shepherd. Despite the (logical but erroneous) interpretations proposed by Alexis, Astrée remains convinced that Céladon is dead. Yet recognition seems imminent since Astrée has called Céladon.

11  In the posthumous fifth volume of 1625, Astrée and Céladon are brought closer.

In the posthumous fifth volume of 1625, Astrée and Céladon are brought closer.

Forez is in a state of alert. The danger comes from a Forezian knight, Polémas. The man who wished to marry Galathée now wants to take over the government. He kidnaps Adamas' daughter to punish the druid. Having once again exchanged their garments, Astrée and Alexis both claim to be Adamas' daughter and end up in jail. They are released by Semire, a soldier of Polémas, who is none other than the shepherd responsible for the separation of the young couple in the first volume. Semire immediately recognizes Céladon and says his name in front of Astrée. The shepherdess still manages to interpret what she hears as a confirmation of Céladon's death.

11-1  In the Vraye Astree by Balthazar Baro in 1627,

In the Vraye Astree by Balthazar Baro in 1627,

The so-called secretary copies most adventures previously published in 1624, however he censures the frolics of Astrée and Alexis.

11-2  In Balthazar Baro's Conclusion, Astrée and Céladon are re-united thanks to a magic spell,

In Balthazar Baro's Conclusion, Astrée and Céladon are re-united thanks to a magic spell,

a short-cut that d'Urfé would have despised.

The young people go to Marcilly. Adamas recommends that Céladon-Alexis reveal his true identity to Astrée. However, Polémas attacks the city. Pretending to withdraw to pray, Céladon-Alexis fights. Polémas is defeated. Céladon, wounded, hides his identity even from the surgeon. Adamas reveals the truth to Astrée. The humiliated and mortified shepherdess orders the young man to die.

To kill himself, Céladon challenges the beasts guarding the fountain of Truth in love. He discovers Astrée fainted. Filled with remorse, the young woman had planned to meet that same fate. The lions fight each other and are transformed into stone. In a clap of thunder the Love God appears to announce an oracle for the following day. Astrée and Céladon are reconciled. A few days later, the inhabitants of the hamlet and the castle parade before the now available fountain of Truth in love. Many couples celebrate their union.

12  The Major Supporting Plot: Diane and Silvandre.

The Major Supporting Plot: Diane and Silvandre.

This love affair has two special characteristics. First, it is not inserted in a secondary story. Diane and Silvandre begin to love each other before our eyes in real time. Secondly, this relationship demonstrates that facts sometimes contradict Silvandre's theories. The young man claims categorically that true love must survive death. Luckily for him, Diane does not remain faithful to the memory of her deceased first love. Silvandre asserts that jealousy is the opposite of love; experience proves that these feelings coexist.

13  In the first volume, Diane and Silvandre discover each other.

In the first volume, Diane and Silvandre discover each other.

Silvandre, a foundling, left Savoie and went to Forez to obey an oracle: the fountain of Truth in love must reveal to him the secret of his origins. He dresses as a shepherd and lives in the hamlet waiting for the fountain to become accessible. Diane also approaches Lignon's shepherds after experiencing tragic adventures. She tells her story to her new friends.

Invasions have separated Diane from her family. Following the abduction of her brother, her father died and her mother became a druidess. Diane is married to Filidas. She does not know that her husband is a girl who passes for a man. Diane discovers love when she meets Filandre. He swaps clothes with his sister to stay close to Diane. Filidas and Filandre die violently defending Diane, coveted by a Moore knight.

Phillis accuses Silvandre of being insensitive to love. The young man defends himself by saying that he does know how to love. Astrée then suggests a competition. Who will love Diane better, Silvandre or Phillis ? Rivals have three months to demonstrate their expertise. Silvandre quickly falls truly in love with Diane.

14  In the second volume, Diane and Silvandre are in love with each other.

In the second volume, Diane and Silvandre are in love with each other.

Pretending to pretend, Silvandre shows his true feelings. Diane, on the other hand, explains to Astrée that, despite her attraction to the young man, she will never marry him because he does not know his parents. She does not, however, reject his love, since she offers him a bracelet made with her hair.

The son of the druid Adamas, Paris, comes to the hamlet with Léonide, his cousin. He falls in love with Diane, but she likes him only as a brother.

15  In the third volume, Diane moves away from Silvandre.

In the third volume, Diane moves away from Silvandre.

To end the playful competition that has lasted more than six weeks and that harms the interests of his son, Paris, Adamas forces Diane to pronounce her judgment. Diane decrees that Phillis is more lovable but Silvandre knows better how to make himself loved. Multiple interpretations of this clever verdict are explored.

The shepherdess Laonice, to avenge a judgment rendered against her by Silvandre in the first volume, slanders the young man by claiming that he loves Madonthe and that he left the village with her. Diane is convinced by Laonice's speech. Persuaded that Silvandre prefers another woman, she allows Paris to ask her mother for her hand in marriage.

16  In the fourth volume of 1624, Diane and Silvandre are separated then reunited.

In the fourth volume of 1624, Diane and Silvandre are separated then reunited.

Diane asks Phillis to get back the bracelet offered to Silvandre. Learning about Diane's resentments, Silvandre faints with grief. Diane and her companions discover a branch of mistletoe burned onto his arm.

Silvandre, despaired by Diane's reproaches, consults an oracle. The Gods tell him that he must die and that Diane will marry Paris. Silvandre cries while reporting this dire prediction to his friends. Phillis gives him a likely and optimistic interpretation.

Diane reconciles with Silvandre as soon as she hears Laonice boast of having slandered the young man.

17  In the posthumous fifth volume of 1625,

In the posthumous fifth volume of 1625,

The relationship between Diane and Silvandre does not evolve.

17-1  In Balthazar Baro's Conclusion, Diane and Silvandre are re-united by a magic spell.

In Balthazar Baro's Conclusion, Diane and Silvandre are re-united by a magic spell.

Silvandre wants to kill himself. He goes with Céladon to the fountain of Truth in love. The two shepherds find Diane and Astrée unconscious. They fight with the lions to protect the young girls. The Love God appears. The next day, he pronounces an oracle: Adamas must kill Silvandre. When the druid sees the branch of mistletoe on Silvandre's arm, he recognizes his long lost son. Diane will marry Silvandre.

18  The Main Aristocratic Plot: The Loves of Galathée

The Main Aristocratic Plot: The Loves of Galathée

Galathée falls in love successively with Polémas, Lindamor and Céladon. She also seems tempted to fall in love with Damon d'Aquitaine.

19  In the first volume, Galathée falls in love three times.

In the first volume, Galathée falls in love three times.

As a little girl in Marcilly, Galathée listens carefully to the stories that druids tell her father. Fascinated by the country's origins, she is proud to bear the name and wear the clothes of a mythical Galathée who married the Gallic Hercules. She is heiress to the throne, because in the Forezian political system, only women are heads of state.

Polémas, a knight at the Court, is in love with Léonide. When Galathée sees the happy couple in the garden, she summons the young girl and orders her to get away from Polémas. Galathée herself seduces the knight.

As a result of a draw organized by Clidaman, Lindamor is authorized to woo Galathée. This knight, younger than Polémas, wins the heart of the nymph. Lindamor and Galathée send each other love letters thanks to a gardener. Jealous, Polémas claims that Lindamor boasts to be the Princess' favorite. Lindamor, disguised as an anonymous knight, jousts against his rival. At the request of Galathée, he spares the life of his opponent. The Princess thinks that the unknown knight did not stop fighting fast enough.

When Galathée discovers the identity of the victorious but seriously injured knight, she refuses to write him a letter. Léonide, because she likes Lindamor or because she hates Polémas, claims that Lindamor died and sent his heart to Galathée. Disguised as a gardener, Lindamor presents a very living heart to the Princess. Galathée promises to marry Lindamor as soon as her brother, Clidaman, takes a wife.

Polémas uses the services of Climanthe to regain Galathée. Neither knight nor Forezian, Climanthe is a mysterious character of great skill. He discovers that Lindamor will wear a green coat on the day he leaves Marcilly to fight in the Franks army. Climanthe then dresses as a druid, settles in the woods, and claims to predict the future. The fake druid announces to Galathée that a man in a green coat must make her misfortune. Three days later, Climanthe shows the Princess the reflection of a picture he painted. It is the place where Galathée will find a "diamond" she must take and keep. Galathée believes the fake druid.

The fateful place is at Isoure along the banks of Lignon. There, Galathée with her favorite companions, Léonide and Silvie, discovers the unconscious Céladon. The nymphs take the shepherd to the palace. Galathée falls in love with him, writes to him, and then openly declares her passion. As the shepherd languishes despite all the efforts of his hostesses, Léonide seeks the help of her uncle, the druid Adamas. With the complicity of Léonide, the druid gives Céladon women's clothes to wear in order to leave the palace unnoticed by Galathée.

20  In the second volume, the loves of Galathée stagnate.

In the second volume, the loves of Galathée stagnate.

When she finds out that Céladon escaped, the Princess is furious. She suspects Léonide to be an accomplice and expels her from the palace. Humiliated by the obvious indifference of her beloved shepherd, Galathée languishes.

A letter from Lindamor asserts that the knight wants revenge on whoever stole Galathée's heart. The Princess fears for Céladon. She wishes that Lindamor and Polémas fight and kill each other. She could then marry Céladon as soon as she succeeds her mother at the head of Forez.

21  In the third volume, Galathée travels around.

In the third volume, Galathée travels around.

Concerned by bad dreams, Galathée consults an oracle at Montverdun. She learns she has to beware of a love passion that will turn into rage.

She sees a foreigner, Damon d'Aquitaine, fight against a cousin of Polémas who insults women. The foreigner kills the Forezian knight.

Galathée was hoping to meet the Lignon's shepherdesses. She does not have time to wait, because her mother asks to see her at the home of Adamas. A knight of Lindamor, at the request of Amasis, tells a story to report the death of prince Clidaman.

Amasis is worried. She has discovered that Polémas exchanges letters with Gondebaud, King of the Burgundians. Adamas must join the nymphs at Marcilly with his daughter and his niece.

22  In the fourth volume of 1624, Galathée is waiting.

In the fourth volume of 1624, Galathée is waiting.

Galathée is reconciled with Léonide. Climanthe reappears disguised as a druid. To procrastinate, the nymphs claim they will consult him again. Polémas prepares his army.

23  In the posthumous fifth volume of 1625,

In the posthumous fifth volume of 1625,

Léonide wears Galathée's clothes to deceive Climanthe. Polémas kidnaps Léonide but the nymph manages to escape. When arrested, Climanthe kills himself. Polémas establishes an alliance with the King of the Burgundians to attack Marcilly.

23-1  In the Conclusion of Balthazar Baro,

In the Conclusion of Balthazar Baro,

Galathée and Lindamor are reunited. Lindamor fights Polémas, who is killed. Galathée celebrates by dressing as a shepherdess. She reunites with Lindamor, the partner revealed by the fountain of Truth in love.

Astrée and Céladon fall in love at first sight and cannot avoid feminine mistrust and male schizophrenia. Their friends, Diane and Silvandre, illustrate that knowledge leads to love, but that female jealousy endangers the relation. Galathée, meanwhile, embodies a tyrannnical love with its spectacular turn of events. For other characters still, loving can feel like walking "on leaning ice" (IV, 4, 824). Next to this multitude of lovers, evolves Hylas, called "brouillon d'amour," beacause his love is just a draft of true love (I, 8, 239 verso). Saint-Marc Girardin is astonished: "Nowhere is inconstancy more spiritually advocated than in this novel devoted to the glory of honest and faithful love" (p. 79). Hylas or the living paradox.

Hylas love life

Hylas love life

Thanks to his fluctuating social condition, thanks to his travels, thanks to the love stories he lives and those that he narrates, Hylas meets with ladies and shepherdess, in Camargue, Lyon, Gergovie and Forez. Being unselective, he goes from one love at first sight to another; he ignores jealousy; since leaving Lyon, he disregards lies. Being audacious and clever, he modifies laws written in the name of the god Love. Admittedly, Hylas is not one of the novel pillars; he is rather like a draft, he who dresses up as wind and sings: "To love for an hour, is to love for a long time" (III, 2, 49 verso). Jean de La Fontaine, however, is not wrong to regard him as "more necessary in the novel than a dozen Céladons" (p. 99).

Hylas is, like Honoré d'Urfé, an extraordinary storyteller who likes to entertain an audience. He recounts his love life by interlocking it with the adventures of those who confide in him. As he likes to enumerate the women he loved, I imitate him here, adding numbers to enlighten the readers.

| FIRST VOLUME | 1. Carlis | |

| 2. Stilliane | ||

| 3. Aimée | ||

| 4. Floriante | ||

| 5. Cloris | She tells him her story | |

| 6. Circène | Hylas falls in love with a voice that sings and then forgets it | |

| 7. Madonthe | ||

| 8. Laonice | ||

| SECOND VOLUME | 9. Palinice | |

| 10. Circène | ||

| 11. Parthénopé | ||

| 12. Florice | ||

| 13. Dorinde | ||

| 14. Criséide | She tells him her story | |

| 15. Phillis | ||

| 16. Alexis | ||

| TRIRD VOLUME | 17. Stelle | The only relationship that does not start with love at first sight |

| FOURTH VOLUME | - |

With his latest passion, a fickle young widow, Hylas signs a contract that is mostly an anti-contract. The partners agree to keep their freedom. How long can this tailored idyll last ? The couple is not mentionned in L'Astrée of 1624; Hylas meets new male friends.

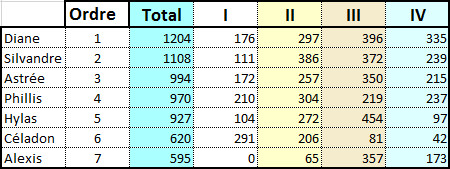

23-3 When I selected and ranked the main characters, I counted on my knowledge as a regular reader of L'Astrée. Exact data processing gave me a lesson in humility by showing who Honoré d'Urfé's « main » characters are (See Dictionnaire des fréquences)... It is up to the readers to decide.

When I selected and ranked the main characters, I counted on my knowledge as a regular reader of L'Astrée. Exact data processing gave me a lesson in humility by showing who Honoré d'Urfé's « main » characters are (See Dictionnaire des fréquences)... It is up to the readers to decide.

24  The sage Adamas - whose story d'Urfé did not get the time to write - sums up this immense novel in a few words. Acting as the author's agent, the druid explains to Céladon the achievements of Love, "the greatest and most holy of all gods":

The sage Adamas - whose story d'Urfé did not get the time to write - sums up this immense novel in a few words. Acting as the author's agent, the druid explains to Céladon the achievements of Love, "the greatest and most holy of all gods":

For all these jealousies, all these contempts,

all these relations, all these quarrels, all these infidelities,

and, in short, all these breakups,

what do you think, my child, they are ?

Punishments sent by this great God.

(L'Astrée, II, 2, 120-121).

L'Astrée presents adventures and misadventures as penalties inflicted on those who do not love well.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Since 2000, a number of people have contributed to the conception and the construction of Two Faces of L'Astrée. I am very grateful to Tufts University for the invaluable support I received, and for giving a home to my website. My deepest gratitude goes to the Faculty Research Awards Committee and to the chairmen of the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, in particular Professor John Fyler and Professor José Antonio Mazzotti.

Thanks also to Tina Riedel and David Bragg from the Information Technology Services, to Anne Sauer and Robert Chavez from the Digital Collections and Archives Department, and to Naomi Marr from University Relations. I appreciated their patience, which I have often tested. I warmly thank Tisch Library and all the past and present librarians who have helped me, especially Chris Barbour, Chao Chen, AnnMarie Ferraro and Laura Walters. I wish to say my gratitude to Professor Joanne Phillips (Classics Department) and to David Proctor (Graduate student, Classics Department) for their careful translations of Greek texts.

I am as well indebted to patient and helpful advisors outside Tufts. I am grateful to Mark Olsen (ARTFL Project, University of Chicago), Prof. Dr. Peter Fuhring (Conseiller scientifique, Fondation Custodia), Jean-Marc Chatelain (Conservateur, Bibliothèque Nationale de France), Marie-Odile Germain (Conservateur, Bibliothèque Nationale de France) and Sylvie Bleton (Chargée de la Reproduction, Bibliothèque Nationale de France) who were kind enough to answer my many questions. I am extremely grateful to Alain Naigeon who kindly agreed to put his talents at the service of L'Astrée: he composed and played dances that charmed Honoré d'Urfé. I wish to express my gratitude to Henri Coulet (Professor emeritus, Université d'Aix-en-Provence, France) who helped me navigate the meanders of sixteenth century language combined with those of a French edition. I would like to especially thank Sue Reed (Curator, MFA, Boston). She has been the best art history teacher and guide. I am also very grateful to Max Vernet (Professor emeritus, Queen's University, Canada) for examining this website. His science and his conscientiousness have been very helpful.

Without the extraordinary assistance and unfailing generosity of my brother, Fekri Henein, Two Faces of L'Astrée would still be in gestation.

A year after writing my first Acknowledgements, I have the duty and the pleasure to add names of people who helped me with advices, commentaries, critiques and suggestions.

In Goutelas, people from Forez and friends of Forez gave me even more than I asked (that's saying a lot!).

My thanks go, in alphabetical order, to Laurent Barnachon, Paul Bouchet, Roger Chazal, Sabine and André Cheramy, Marc Delacroix, Mireille Delmas-Marty, Patricia Faye-Chazal, Reinhard Krüger and his students, Marie-Claude Mioche, Mr. and Mrs. Niedermeyer, Alfred and Christine Noé, and Thomas Poiss.

In Paris, I benefited from remarks made by Christine de Buzon, Michel Fournier, Paule and Udo Koch, Tatiana Kozhanov, Marie-Gabrielle Lallemand, and Marta Teixeira Anacleto.

Thanks to the Internet, I had fruitful exchanges with Christian Allègre, Étienne Brunet, Arnaud Bunel, Joseph Casazza, Catherine Faivre d'Arcier, Hervé Mondon, Buford Norman, Maxime Préaud, Joseph Salvi, and Dominique Tailliez. I also benefited from advices given by the managers of two French bookstores « Le Bateau Livre » (Montpellier) and « Librairie Pierre-Josse » (Charcé).

In the United Sates, Christiane Romero answered my call for help. Charles Dietrick and Mike Lupi made my website easier to access. Nancy Mimno, with great dedication, helped me transfer my files to the new address.

All those who used Two Faces of L'Astrée and who can appreciate its easily navigated multilayered structure will understand that I reiterate here my gratitude to my brother, Fekri Henein.

I owe my deepest gratitude to several French institutions that gave me the possibility to offer today this edition of a Seventeenth century novel. I will not start with Napoleon and the foundation of French schools in Egypt, but I acknowledge with pleasure and emotion that I owe a lot to the Pensionnat du Sacré-Cœur, to the Cultural services in Cairo and in Boston, and to the Sorbonne, my Alma mater. I hope their representatives, and especially Jacques Fauve, will find here my deepest gratitude.

Thank you very much to all those who helped me unravel the second volume of L'Astrée. This critical edition would be less comprehensive without the generous help and support of Paul Bouchet, Arnaud Bunel, Joseph Casazza, Jean-François Cottier, Marc Delacroix, Michel De Waele, Giovanni Dotoli, Jacques Elfassi, Henriette Goldwyn, Martin Howard, Pierre Kunstmann, Michel Lemaire, Martial Martin, Jacques Messier, Marie-Claude Mioche, Alfred Noé, Buford Norman, David Russel, Marie-Rose Salloum, David Seipp, Marta Teixeira Anacleto, Bruno Tribout and Karen-Dominique Villiaume. Emmanuel Bury, Alexandre Gefen and Françoise Lavocat offered very useful comments.

Thank you to those who allowed me to include part of their websites, Francis Boucher, Jacques Leclerc, Nicolas Liger and Valérie Potier.

Thank you to the Bibliothèque municipale de Versailles, and especially to Élisabeth Maisonnier and Anne-Bérangère Rothenburger.

Thank you to Tisch Library (Tufts University), and especially to Chao Chen, AnnMarie Ferraro and Laura Walters.

Thank you to the Information Technology Services, at Tufts and elsewhere, and especially to Alyssa Krimsky Clossey, Charles Dietrich, Neal Hirsig, Shawn Maloney, Peter Sanborn and Robert Thomas.

Thank you to all those who sent me messages.

Special thanks to Aleksey Svetlichny, author of the Galerie.

Thanks again to Fekri Henein for his crucial support. He makes miracles to provide Two Faces of L'Astrée with all the assets of electronic technology.

I'm very fortunate. Since 2010, help has come from many directions.

My gratitude goes to the librarians and curators who have supported my endeavour. Meeting experts who do not consider books as museum pieces and researchers as intruders has been a comfort and a joy.

Thank you to Thierry Conti (L'Alcazar, Bibliothèque municipale de Marseille), Sally S. Dickinson (Watkinson Library, Trinity College, USA), Annemarie Kaindl (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich) and Bruno Marty (Centre de Conservation du Livre, Carpentras).

Thank you to the Tisch librarians (Tufts University): I know I can always count on the help of Chen Chao, AnnMarie Ferraro, Connie Reik, Laurie Sabol and Laura Walters.

My sincere gratitude goes to those who sent me the echoes of the past preserved in the Archives of Ain (Fanny Aznar, Gilles Philibert, Fabienne Silvestre, Valéry Vesson), of Alpes-Maritimes (Hélène Cavalié, M. Coutelier), of Ariège (Christine Massat, Caroline Piquemal, Jean Cairo, Martine Patet), of Savoie (Sylvie Claus, Anne Vacchiero),

of Torino (Maria Barbara Bertini, Maria Gattullo), and of the Musée Savoisien (Laurence Sadoux-Troncy).

A very warm thank you to my friends, Christiane Fabricant and Uta Reese, who generously worked on archival documents in Foix.

My gratitude goes to those in charge of libraries, bookstores and websites for ancient books:

Les Bibliothèques Virtuelles Humanistes (Mme le Professeur Demonet and Sandrine Breuil), The Smithsonian Institute (Elizabeth Aldrich, Anne McLean, Virgina Clark, Cynthia Field and Jonathan Kemper), Penn State University (Karen Schwentner), and La Médiathèque de Roanne (Christine Henry and Audrey Mancini). Thank you also to Mohamed Graine (Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon), to Christian Pellet

(Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, Lausanne), Dale Tatro (Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.), and the Librairie Le Passe-Temps.

I am especially grateful to Lia Poorvu, a colleague and a friend ready to help on all occasions in order to establish contacts.

Thank you again and again to those who allow me to hear the voice of Forez and its surroundings:

Laurent Barnachon (Conseil général de la Loire), Joseph Barou (Forez histoire), Sandrine Beal (La Bâtie d'Urfé), Françoise Bourlot (Observatoire de l'eau), Sophie Chauve (Communauté d'Agglomération Loire Forez),

Pierre Grès (Fédération de pêche de la Loire), Pierre-Jean Martinez (DREAL Rhône-Alpes), Marie-Claude Mioche

(Centre Culturel de Goutelas), and Xavier de Villele (SYMILAV, Savigneux).

I express my profound gratitude to my colleagues for their advice and expertise:

Francis Assaf (University of Georgia), Benoît Bolduc (New York University), William Brooks (University of Bath, U.K.), Fanny Cosandey (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales), Marc Court (Paris-Sorbone, Paris-IV), Dominique Descotes (Université Blaise-Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand), Mark DeVoto (Tufts University), Gérard Ferreyrolles (Paris-Sorbonne), John Fyler (Tufts University), Richard Goodkin (University of Wisconsin-Madison), Nicolas Graner (Université Paris-Sud), Elizabeth T. Howe (Tufts University), Reinhard Krüger (Universität Stuttgart), Bruno Méniel (Université de Rennes 2), Alfred Noé (Universität Wien), Jean-Michel Roessli (Concordia University, Canada), Daniel Russel (University of Pittsburgh), Marc Surgers (Consultant, Paris), Bruno Tribout (University of Aberdden), Daniel C. Weiner (Boston University).

I reiterate my thanks to generous Internet users:

Jean-Pierre Augier, Jean-Michel Chaumont, Philippe

Desterbecq, Jean-Bernard Elzière, Jacky Lorette, Marcel Martinod,

Jocelyne Muguet,

Jean-Claude Rolland and Pierre Wechter (Scribd.). I can never thank enough Arnaud Bunel, the knowledgeable webmaster of Héraldique européenne.

I have always received the support I needed from my friends. Thank you to Cécile Créhange, Lois Grossman, Rémy Oppert, Sue Reed (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Jean-Pierre Reverseau (Musée de l'Armée, Paris), Emese Soos, and Karen Villiaume.

Thank you to Christian Allègre who reviewed this electronic critical edition and made precious suggestions.

Thank you to Guy Perron, palaeographer, to the translators, Lise Beeotis and Marion Valdoni, and to my editors, Jason Lenicheck and Lucy Fyler.

Thank you to those who wrote to me. Their kind and supportive messages mean a lot to me.

He who does not want to be recognized

is someone who deserves all your gratitude

Guizot (Article Reconnaissance).

Although my brother, Fekri Henein, did not wish to be named once more in these acknowledgements, I have to award him the place of honour he deserves. Thanks to him this website remains user friendly. In the name of all lovers of L'Astrée and on my own behalf, I would like to reiterate my thanks in particular for the invaluable Index des noms propres he composed and for the detailed Guide. His skills cleverly organized the visual space of Two Faces of L'Astrée and improved this constantly growing critical edition.

Merci, action de grâces, ex-voto, gratitude, reconnaissance ...

I am always looking for synonyms to say my gratitude to Étienne Brunet, emeritus professor (Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis), distinguished and generous lexicologist. Thanks to him, my edition of L'Astrée rubs shoulders with the most prestigious works of French literature in his Hyperbase.

I thank Christine de Buzon (Professeur des Universités) who suggested that I ask for assistance from Professor Brunet, and I thank my brother who has remedied my weakness in mathematics.

I take this opportunity to say also my appreciation to Pierre Arette-Hourquet, Jean-Luc Buathier, Hélène Cavalie, Didier Coste, Pierre Dubreuil, Jean-Baptiste Glodin, David Gullentops, Chris Hill, Masviel Jimdo, Martha Kelehan, Marie-Pierre Mahtey, Pierrot Métrailler, Rémi Mogenet et Peter Simon.

I reiterate my thanks to Tufts University, to the Romance Studies Department, in particular to its chairman, Pedro A. Palou.

Thank you very much to librarians at several institutions:

Guichet du savoir (Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon), Catherine Bernier (Université de Montréal, Bibliothèque des lettres et sciences humaines), Susan Brady (Tisch Library, Tufts University), Anna Buck (The Warburg Institute Library), Thierry Conti (L'Alcazar, Bibliothèque de Marseille), Jonathan Jara (Columbia University Libraries) and Charles-Eloi Val (Sinbad, BnF).

A special Thank you to Steve Garrett and Kevin Summers (TTS).

Thank you very much to those who have answered my questions for many years: Christian Allègre, Christine de Buzon, Bruno Marty, Marie-Claude Mioche, Alain Naigeon, Alfred Noé and Jean-Pierre Reverseau.

Thank you also to:

Maria Barbara Bertini (Archives de Turin),

Nicolas Delpierre

(Archives de l’Université catholique de Louvain),

Kirsten Dickhaut (Romanische Literaturen I, Universität Stuttgart),

Anne Hoguet (Musée de l'éventail),

Elena Malaspina (Universita Roma 3, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici),

Lionel Mancier (Médiathèques de Saint-Étienne),

Fabian Mauch (Web administrator, Institute of Literary Studies, Universität Stuttgart),

Konrad Niemira

(University of Warsaw / DESA Unicum Warsaw),

Nolwenn Pavlin (Centre Culturel de Goutelas),

Marie-Lauence Viel (Médiathèque du Mans),

Marcello Vitali-Rosati (Université de Montréal),

Edwige Zanoguera (Médiathèque de Tarentaize).

A special thank you to Étienne Brunet (Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis).

Thank you to those who wrote to me.

Thank you very much to my brother, Fékri, who tirelessly finds new ways to improve this website.